Archaeology

Part i: Archaeological Research in the Coastal Plain; Part ii: Discoveries of the North Carolina Piedmont; Part iii: Mountain Archaeological Sites and Discoveries; Part iv: Underwater Archaeology

Part IV: Underwater Archaeology

Underwater archaeology was first conducted in North Carolina in the early 1960s, when U.S. Navy divers, working in cooperation with the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, recovered several thousand artifacts from sunken Civil War blockade-runners in the Wilmington vicinity. In 1963 the state established a preservation laboratory at the Fort Fisher State Historic Site to treat those artifacts, and in 1967 the General Assembly passed a law to protect submerged cultural resources in the state. That statute claimed North Carolina's ownership of all cultural material unclaimed in state waters for more than ten years. Further, the law authorized the Department of Cultural Resources to establish a professional staff and regulations for managing those submerged resources, and to develop a system for permitting qualified individuals, groups, and institutions to conduct investigations and recovery projects of underwater archaeological sites.

Underwater archaeology was first conducted in North Carolina in the early 1960s, when U.S. Navy divers, working in cooperation with the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, recovered several thousand artifacts from sunken Civil War blockade-runners in the Wilmington vicinity. In 1963 the state established a preservation laboratory at the Fort Fisher State Historic Site to treat those artifacts, and in 1967 the General Assembly passed a law to protect submerged cultural resources in the state. That statute claimed North Carolina's ownership of all cultural material unclaimed in state waters for more than ten years. Further, the law authorized the Department of Cultural Resources to establish a professional staff and regulations for managing those submerged resources, and to develop a system for permitting qualified individuals, groups, and institutions to conduct investigations and recovery projects of underwater archaeological sites.

The North Carolina Underwater Archaeology Unit maintains extensive files on over 4,000 historically documented shipwrecks, as well as a wide variety of water-related subjects such as bridge and ferry crossings, historic ports, plantation landings, riverine and coastal trade, harbor development, and improvements to navigation. Historical research can be used to define a search area where a specific shipwreck should be located or to identify a site that has been located by other means. Over the past three decades, researchers have documented more than 700 underwater archaeological sites in North Carolina that include prehistoric dugout canoes, colonial sailing vessels, beached shipwreck remains, dozens of Civil War shipwrecks, and nineteenth- and twentieth-century steamboats.

Underwater archaeologists use a variety of means to locate and document shipwrecks and other submerged sites. Occasionally, sites can be visually observed in shallow water and are reported by fishermen, boaters, or recreational scuba divers. To locate shipwrecks in deeper water, archaeologists rely on remote sensing equipment such as magnetometers and side-scan sonar. The remote sensing equipment is operated from a research vessel that systematically searches the survey area. Ideally, an electronic positioning system is used to maintain and record the vessel's position during the survey.

The position of all artifacts must be carefully recorded, and, once recovered, the artifacts should be stored in water until they reach the preservation laboratory. A variety of methods are employed to stabilize artifacts recovered from an underwater environment, depending on the composition of the material and whether it came from fresh or salt water. Waterlogged organic materials, such as wood, are normally preserved by replacing the water with a bulking agent such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) or sugar. Ferrous metals are ordinarily stabilized through electrolytic reduction. For large objects, like cannons, this process can take several years to complete.

References:

George F. Bass, Ships and Shipwrecks of the Americas: A History Based on Underwater Archaeology (1988).

Linda Crawford Culberson, Arrowheads and Spear Points in the Prehistoric Southeast: A Guide to Understanding Cultural Artifacts (1993).

Mark A. Mathis and Jeffrey J. Crow, eds., The Prehistory of North Carolina: An Archaeological Symposium (1983).

Theda Perdue, Native Carolinians: The Indians of North Carolina (1985).

Burton L. Purrington, Ancient Mountaineers: An Overview of the Prehistoric Archaeology of North Carolina's Western Mountain Region (1983).

Trawick H. Ward and R. P. Stephen Davis Jr., Time before History: The Archaeology of North Carolina (1999).

Additional Resources:

North Carolina Office of State Archaeology. http://www.archaeology.ncdcr.gov/ (accessed October 9, 2012).

"A Brief History of North Carolina Archaeology." University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Research Laboratory of Archaeology. http://rla.unc.edu/archaeonc/time/briefhistory.htm (accessed October 9, 2012).

"Voices of the Sandhills: Archaeology." Fort Bragg. 2010. http://www.voicesofthesandhills.com/archaeology/ (accessed October 9, 2012).

Queen Anne's revenge: laboratory excavation report. North Carolina State Office of Archaeology, Underwater Archaeology Unit. August 2002-September 2010. https://cdm16062.contentdm.oclc.org/u?/p249901coll22,63754 (accessed October 9, 2012).

Bollinger, Catherine E. Guide to research papers in the archaeology of North Carolina on file with the Archaeology Branch of the North Carolina Division of Archives and History. North Carolina. Division of Archives and History. Archaeology Branch. 1981. https://cdm16062.contentdm.oclc.org/u?/p249901coll22,63754 (accessed October 9, 2012).

Image Credits:

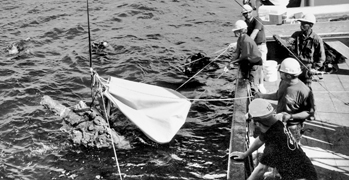

Archaeologists on a recovery ship secure a 763-pound cannon brought to the surface by divers from a wreck believed to be Blackbeard's flagship, the Queen Anne's Revenge, which sank in Beaufort Harbor in 1718. The site, discovered in 1996, yielded a wide variety of artifacts as well as parts of the ship itself. Courtesy of North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh. (accessed October 8, 2012).

Southerly, Chris and Joe Beatty. Flyleaf: Underwater Archaeology in North Carolina. N.C. Dept. of Natural and Cultural Resources, Apr, 13, 2022. Accessed Sept. 28, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/live/E4t5fFFmWxE?si=t1b84KJawNgx-hr6.

1 January 2006 | Davis, R. P. Stephen, Jr.; Freeman, Joan E.; Lawrence, Richard W.