Atkinson, Henry

1782–14 June 1842

Henry Atkinson, military officer, born into a locally prominent family in Caswell, now Person, County. His father, John Atkinson, received land grants from the colonial government in 1748 and 1750. By 1785, his landholdings totaled 6,100 acres in the present Person and Caswell counties. Henry Atkinson's mother, about whom little is known, died shortly after his birth, leaving six children, and John soon afterward married Francis Dickens. When John Atkinson died in 1792, he left two more children, 3,665 acres, and seventeen enslaved people.

Henry Atkinson, military officer, born into a locally prominent family in Caswell, now Person, County. His father, John Atkinson, received land grants from the colonial government in 1748 and 1750. By 1785, his landholdings totaled 6,100 acres in the present Person and Caswell counties. Henry Atkinson's mother, about whom little is known, died shortly after his birth, leaving six children, and John soon afterward married Francis Dickens. When John Atkinson died in 1792, he left two more children, 3,665 acres, and seventeen enslaved people.

John and his sons Edward and Richard all engaged actively in local and state politics. During the Revolution, John served as a delegate to the Hillsborough provincial congress (August 1775), a member of the Hillsborough Committee of Safety, and, at three different times, a member of the House of Commons. In 1781 he became the new state's tobacco purchasing agent. In addition, he was a justice of the peace in Orange County from 1776 to 1788. Edward served as county sheriff and state legislator before his death in 1797. Richard sat in the House of Commons and the state senate.

At the age of eighteen, Henry Atkinson inherited a thousand acres in Caswell County. Two years later he was among the ten trustees who obtained the charter for Caswell Academy, a local free school. He became clerk and then treasurer of the school's board of trustees. In 1804–5 he ventured into commerce, establishing a small store, but the business failed. Whether his agricultural enterprises failed similarly or whether he merely felt disinclined to continue the life of a planter is uncertain, but in either case, Atkinson entered the U.S. Army on 1 July 1808 as a captain in the Third Infantry.

Atkinson spent his first five years of military service in routine duties along the Lower Mississippi River and the Gulf Coast. His activities there presaged much of his later career. Although Atkinson rose to become one of the senior commanders in the West after the War of 1812, he was rarely involved in combat; most of his life was devoted to the historically unspectacular but nonetheless vital administration of a frontier army in times of relative peace.

One year after the outbreak of the war with Britain, Atkinson was appointed brevet colonel and inspector general in the Ninth Military District. His new assignment took him to the Northeast, where he remained for five years. Although the New York-Vermont theater of war was more explosive than the Gulf theater at the time of Atkinson's transfer, the young officer led no troops in battle. He did receive his first command, the Thirty-seventh Infantry, in April 1814, after a one-week paper command of the Forty-seventh. His task, however, was to provide for the coastal defense of Connecticut. With the Thirty-seventh in the New London area and, after the war, with the Sixth Infantry at Plattsburgh, N.Y., he concentrated on drilling, fort-building, and road construction, activities that were to consume much of his time on the western frontier.

In 1818, Atkinson was placed in command of the military district consisting of Kentucky, Tennessee, and the Missouri Territory, and he and the Sixth moved west. Although the territory underwent frequent nominal changes and his own supervision varied from a de jure to a de facto one, this vast frontier area was to be Atkinson's predominant domain until his death in 1842.

The colonel's first major undertaking was leading one column of a three-pronged exploratory expedition initiated by Secretary of War John C. Calhoun. He progressed as far as Council Bluffs, where he constructed an outpost that Calhoun later named Fort Atkinson, before Congress terminated funding for the project in the wake of the Panic of 1819.

The colonel's first major undertaking was leading one column of a three-pronged exploratory expedition initiated by Secretary of War John C. Calhoun. He progressed as far as Council Bluffs, where he constructed an outpost that Calhoun later named Fort Atkinson, before Congress terminated funding for the project in the wake of the Panic of 1819.

In the army reorganization of 1821, Atkinson lost his district command, but his friends in Washington helped him retain his colonelcy and his post as head of the Sixth Infantry. Although subordinate to General Edmund Gaines, Atkinson continued to oversee his old area of jurisdiction, now placed in his charge as the Right Wing. His leadership in securing the frontier lasted until the mid-1830s.

Atkinson's primary responsibility in the 1820s was negotiation with the Indians, who called him "White Beaver." He showed a certain conciliation and finesse in these dealings. Until the Black Hawk uprising, he avoided physical conflict between the army and the Indians through effective manipulation of a show of force in conjunction with negotiation. One of his premier accomplishments was his leadership of an expedition from St. Louis to the mouth of the Yellowstone River in 1825. He negotiated twelve treaties with sixteen bands of Indians and, using paddle wheel keelboats for the first time on a military venture, suffered no serious damages to the boats and lost no men.

In the next two years, under directions from Gaines, he selected the site for and supervised the construction of a new army infantry school, over which he was to exercise personal control, at Jefferson Barracks, Mo. From that time on, Jefferson Barracks was his home, and he divided his time between frontier problems and infantry instruction.

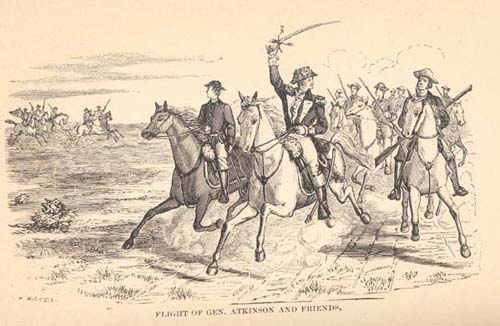

His sole command of troops in combat came in 1832. The Sauks under Black Hawk tried to recross the Mississippi River to lands in Illinois they had surrendered to the United States in the Corn Treaty of 1831. Atkinson apparently overemphasized the dangers inherent in the situation. He prompted Illinois's Governor John Reynolds to call out an undisciplined militia and refused to parlay with the Indians. His cautious pursuit of Black Hawk evoked criticism from Washington, and General Winfield Scott was ordered to assume command with fresh troops. However, Scott's men were stricken by an epidemic of Asiatic cholera before departure and so Atkinson was left to conduct the campaign. After two months of exasperating, unrewarding marching, Atkinson caught up with the Sauks and soundly defeated them at Bad Axe, Wisc., on 2 Aug.

During July, Atkinson had been forced to encamp and await provisions. At the juncture of the Bark and Rock rivers, his troops constructed a shelter for the sick and supply base, christened Fort Coshconong. After the campaign, the fort was given to friendly Potawatomies, who maintained it for less than a year before being forced to sell all their eastern lands. Within a few years, white settlers occupied the site and constructed the town of Fort Atkinson, Wisc.

The last ten years of Atkinson's life were frustrating ones. Young officers superseded him in the actual command of the expanding frontier. He became chiefly a paper-shuffling intermediary. He grew irascible and evinced signs of approaching senility. In 1838, President Martin Van Buren offered him the first governorship of the new Iowa Territory, but the colonel immediately spurned the appointment without specifying reasons. His last important military achievement was the supervision of the westward removal of the Winnebago Indians to northern Iowa in 1840. In the process, he established the last of three Fort Atkinsons, this one built for the protection of the Sauks and Foxes about thirty-five miles west of Prairie du Chien.

Atkinson married Mary Ann Bullitt in Christ Episcopal Church, Louisville, Ky., on 15 Jan. 1826; a son, Henry, Jr., was born to them the following February. George Catlin painted a portrait of Atkinson in 1824.

Atkinson died of dysentery in his home in 1842 and was buried at Jefferson Barracks. Some time later, his body was reinterred in the Bullitt-Gwathmey family lot in Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville.

This person enslaved and owned other people. Many Black and African people, their descendants, and some others were enslaved in the United States until the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery in 1865. It was common for wealthy landowners, entrepreneurs, politicians, institutions, and others to enslave people and use enslaved labor during this period. To read more about the enslavement and transportation of African people to North Carolina, visit https://aahc.nc.gov/programs/africa-carolina-0. To read more about slavery and its history in North Carolina, visit https://www.ncpedia.org/slavery. - Government and Heritage Library, 2023

References:

DAB, vol. 1 (1928).

Roger L. Nichols, General Henry Atkinson (1965).

Mrs. George Swart, ed., Footsteps of Our Founding Fathers (1964).

Who Was Who in America, 1607–1896.

Additional Resources:

Henry Atkinson, 1782-1842, State Historical Society of Nebraska: http://nebraskahistory.org/lib-arch/research/manuscripts/family/henry-atkinson.htm

Nichols, Roger L. General Henry Atkinson: frontier soldier, 1782-1842. University of Wisconsin--Madison, 1964 - History - 638 pages. http://books.google.com/books/about/General_Henry_Atkinson.html?id=dytSAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed February 7, 2013) or https://www.worldcat.org/title/general-henry-atkinson-frontier-soldier-1782-1842/oclc/14769044

Wisconsin Historical Society: http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/dictionary/index.asp?action=view&term_id=27&keyword=black+hawk

The Encyclopedia of North American Indian Wars, 1607–1890: http://books.google.com/books?id=lyNakUZmQ9IC&pg=PA40&lpg=PA40&dq=Henry+Atkinson+1782&source=bl&ots=WKZoUbwD3Q&sig=Ycg8mhu_2UgKzD3Gr-jwpJF3rEo&hl=en&sa=X&ei=MKcTUfDgFI3-8ATO-oHoBg&ved=0CFkQ6AEwBjge#v=onepage&q=Henry%20Atkinson%201782&f=false&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed February 7, 2013).

Wheel Boats on the Missouri: The Journals and Documents of the Atkinson-O, by Henry Atkinson, Stephen Watts Kearny, Richard E. Jensen: http://books.google.com/books?id=dn5eW976XpgC&pg=PA1&lpg=PA1&dq=Henry+Atkinson+1782&source=bl&ots=ss3WYNOcBC&sig=SxDZ7CVESyF_-Jz3TJatuVQ4Qd8&hl=en&sa=X&ei=MKcTUfDgFI3-8ATO-oHoBg&ved=0CFQQ6AEwBTge#v=onepage&q=Henry%20Atkinson%201782&f=false&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed February 7, 2013).

Image Credits:

Courtesy of the Abraham Lincoln Historical Digitization Project. Available from http://lincoln.lib.niu.edu/ (accessed February 7, 2013).

Aerial view ca. 1957-60 - Jefferson Barracks, Jefferson Barracks, St. Louis County, MO. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.Available from http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/mo0984/ (accessed February 7, 2013).

1 January 1979 | Wiest, Timothy J.