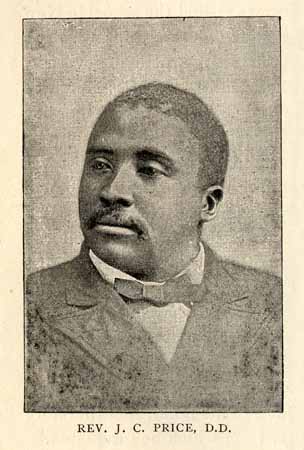

Price, Joseph Charles

by John Inscoe, 1994; Revised October 2022.

Related Entries: Civil Rights; Civil War; African American; Historically Black Colleges and Universities

10 Feb. 1854–25 Oct. 1893

Joseph Charles Price, black educator, orator, and civil rights leader, was born in Elizabeth City to a free mother, Emily Pailin, and an enslaved father, Charles Dozier. When Dozier, a ship's carpenter, was sold and sent to Baltimore, Emily married David Price, whose surname Joseph took. During the Civil War, they moved to New Bern, which quickly became a haven for free black people when it was occupied by Federal troops. In 1863 his mother enrolled him in St. Andrew's School, which had just been opened by James Walker Hood, the first black missionary to the South and later the bishop of the A.M.E. Zion Church. Price showed such promise as a student at this and other schools that in 1871 he was offered a position as principal of a black school in Wilson. He taught there until 1873, when he resumed his own education at Shaw University in Raleigh with the intention of becoming a lawyer. But he soon changed his mind and transferred to Lincoln University in Pennsylvania to study for the ministry in the A.M.E. Zion Church. He was graduated in 1879 and spent another two years at its theological seminary. During this period, he married Jennie Smallwood, a New Bern resident he had known since childhood. They were the parents of five children.

In 1881, soon after his ordination, Price was chosen as a delegate to the A.M.E. Ecumenical Conference in London. While there, Bishop Hood urged him to make a speaking tour of England and other parts of Europe to call attention to the plight of black education in the South and, more specifically, to raise funds to establish a black college in North Carolina. His effectiveness as an orator drew large crowds and resulted in contributions of almost $10,000. This, plus the support of white residents of Salisbury, enabled him to establish Livingstone College and to become its president in October 1882, when he was twenty-eight years old. (Originally called Zion Wesley College, its name was changed to that of the African explorer and missionary David Livingstone in 1885.) Sponsored by the A.M.E. Zion Church, Livingstone began with five students, three teachers, and a single two-story building, but it grew rapidly to become one of the South's most important liberal arts colleges for blacks. Though he encouraged the support of southern whites, such as Josephus Daniels, and philanthropists, such as Leland Stanford and Collis P. Huntington, Price felt that blacks themselves must bear the real responsibility for educating their race. In 1888 he stated that "Livingstone College stands before the world today as the most remarkable evidence of self-help among Negroes in this country."

Price's leadership of the college and his ability as an orator gained him national attention. In 1888 President Grover Cleveland asked him to serve as minister to Liberia, though he declined, saying he could do more for his people by remaining in Salisbury. In 1890 he was elected president of both the Afro-American League and the National Equal Rights Convention and named chairman of the Citizens' Equal Rights Association. But conflict among the groups and lack of financial support led to their decline soon afterwards. Like Booker T. Washington, Price believed that blacks' self-help through education and economic development was their best hope for solving the race problem, and he assured whites that social integration with them was not among their goals. But he was less conciliatory than Washington in demanding that the civil rights of blacks be upheld. Blacks were willing to cooperate and live peaceably with southern whites, but not at the cost of their own freedom of constitutional guarantees. "A compromise," he wrote, "that reverses the Declaration of Independence, nullifies the national constitution, and is contrary to the genius of this republic, ought not to be asked of any race living under the stars and stripes; and if asked, ought not to be granted."

Price's activist role in civil rights and black education ended abruptly in 1893, when he contracted and died of Bright's disease at age thirty-nine. He was buried on the campus of Livingstone College. W. E. B. Du Bois, August Meier, and others felt that it was the leadership vacuum created by Price's death into which Booker T. Washington moved, and that had he lived, the influence and reputation of Price and of Livingstone College would have been as great or greater than that achieved by Washington and Tuskegee.

References:

Annotated Bibliography of Joseph Charles Price (manuscript, Livingstone College Archives, Salisbury, 1956)

Charlotte Observer , 17 Feb. 1970

Durham Sun , 31 Oct. 1970

Greensboro Daily News , 22 Feb. 1960

J. W. Hood, One Hundred Years of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (1895 [portrait])

August Meier, Negro Thought in America, 1880–1915: Racial Ideologies in the Age of Booker T. Washington (1953)

North Carolina Teacher 11 (November 1893)

Stephen B. Weeks Scrapbook, vol. 10 (North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill).

Additional Resources:

NC Historical Markers

WUSA Black History Month Profile: http://www.wusa9.com/news/local/story.aspx?storyid=190526

The New York Times: A Plea for Colored Men...: http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=FA0A16FF3C5515738DDDAA0994D9405B8385F0D3

Image Credits:

Rev. J.C.Price, D.D. 1895. Photo courtesy of DocSouth, UNC. Available from https://docsouth.unc.edu/church/hood100/ill57.html (accessed March 14, 2012).

1 January 1994 | Inscoe, John C.