Catawba Indians

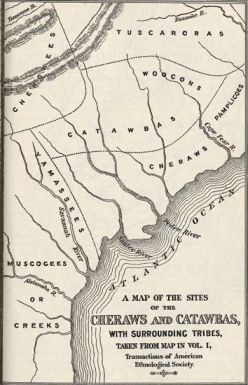

Catawba Indians are often referred to as the Catawba Nation, a term that describes an eighteenth-century amalgamation of different peoples that included the Catawba Indians. Historically, the American Indians who came to be called "Catawba" occupied the Catawba River Valley above and below the present-day North Carolina-South Carolina border. They are descended from a large group of independent peoples in the Catawba Valley who spoke a Siouan language.

From the time of the settlement of Charles Towne (modern-day Charleston, S.C.) in 1670, the Esaw, Catawba, and Sugaree tribes experienced the difficult and disruptive consequences of Euro-American frontier expansion. The politics of trade and settlement, and the concern for protection from other Indians (especially the Iroquois), were the major forces that dictated the Catawba's relations with the Carolina and Virginia colonies. Some historians believe that the location of the Catawba on the trading paths was advantageous in that it enabled them to deal with both Virginia and Charles Towne. Also helpful was the Catawba ability to remain generally neutral during the colonial trading wars between 1690 and 1710. This placed the Catawba in the position of having some control over trading access and also served as a motivation to maintain their position. Those who joined the Catawba often did so for protection, not only from the Iroquois but also from the Catawba themselves.

On the whole, the Tuscarora War (1711-13) and the Yamassee War (1715) proved to be devastating for American Indian people of the Carolinas, including the Catawba. The actions of abusive fur traders and the constant threat of enslavers of American Indian people enraged many of the American Indian tribes, especially those living in proximity to colonial settlements. In 1713 the Catawba actively joined with the Yamassee in a concerted attack against the lowcountry colonists in South Carolina. The onset of the so-called Yamassee War again reflected the abuses and politics of the American Indian trade between the North Carolina and South Carolina colonies. The Yamassee and their allies were savagely repulsed, with many of the smaller American Indian groups disappearing in the aftermath. The Catawba people retreated to their northern towns and again absorbed refugees from the defeated tribes.

The Catawba Nation at the end of the Yamassee War included remnants from as many as 30 other American Indian tribes, among them the Esaw, Saura (Cheraw), Sugaree, Waxhaw, Congaree, Shakori, Keyauwee, and Sewee. Despite the continual influx of refugees, diseases and warfare had taken a terrible toll on the Catawba, and their population in 1728 was believed to have been only around 1,400. A smallpox epidemic in 1738 appears to have killed nearly one-half of the nation's population. During the 1750s, the Catawba were embattled by northern war parties that effectively ended the tribe's ability to compete for deerskins. They lost a series of crops to drought and excessively hot summers, and disease continued to take its toll. The Catawba regained some strength during the French and Indian War, during which they sided with the British. However, a second devastating smallpox epidemic struck in 1759, reducing their population to a mere 500 people.

The Catawba Nation at the end of the Yamassee War included remnants from as many as 30 other American Indian tribes, among them the Esaw, Saura (Cheraw), Sugaree, Waxhaw, Congaree, Shakori, Keyauwee, and Sewee. Despite the continual influx of refugees, diseases and warfare had taken a terrible toll on the Catawba, and their population in 1728 was believed to have been only around 1,400. A smallpox epidemic in 1738 appears to have killed nearly one-half of the nation's population. During the 1750s, the Catawba were embattled by northern war parties that effectively ended the tribe's ability to compete for deerskins. They lost a series of crops to drought and excessively hot summers, and disease continued to take its toll. The Catawba regained some strength during the French and Indian War, during which they sided with the British. However, a second devastating smallpox epidemic struck in 1759, reducing their population to a mere 500 people.

Reeling from the effects of Anglo-American colonization and the epidemic, in 1759 the Catawba gathered together, abandoning their towns around Sugar Creek and establishing a unified town at Twelve Mile Creek. They also negotiated a land deal with South Carolina that established clear title to a reservation 15 miles square. Though they established their reservation, this period marked the beginning of the end of Catawba influence in colonial affairs. When the French and Indian War concluded in 1763, the English colonies had little need for the services of the small and struggling Catawba Nation.

By the time of the American Revolution, the Catawba had adjusted uneasily to their circumstances, surrounded by and living among the Euro-American settlers, who did not consider them a threat. In September 1775, the Catawba pledged their allegiance to the colonies. Catawba warriors fought against the Cherokee and against Lord Charles Cornwallis in North Carolina. When the English captured Charles Towne (1780) and moved north, the Catawbas fled into North Carolina. Upon their return in 1781, they found their village destroyed and plundered. By the end of the eighteenth century, it appeared to most observers that the Catawba people would soon be extinct. By 1826 only 30 families lived on the reservation. Despite constant complaints about unfair settlement within their reservation, the Catawba were granted little to no concessions from the South Carolina government.

Both sides agreed to meet at Nation Ford in March 1840. The Catawba agreed to give up their lands in exchange for a government pledge to spend $5,000 to purchase land for them elsewhere. After an abortive attempt to relocate them near the Cherokee in North Carolina, a 630-acre tract was selected on the west bank of the Catawba River within the boundaries of the old reservation; by 1850, 100 Catawbas were living there.

The small enclave of Catawba Indians persevered through poverty and oppression. Some served with the Confederacy in the Civil War. They remained poor and relatively isolated from their neighbors but retained a strong Catawba cultural identity. During the late 1800s, many Catawba converted to Mormonism and moved to southern Colorado, founding Mormon towns such as Fox Creek, La Jara, and Sanford. During this diaspora period, others of the Catawba left South Carolina for Oklahoma and Texas.

The Catawba maintained their identity into the twentieth century, and in 1941 they became a federally recognized tribe. They chose to terminate their tribal status in 1959, however, and received individual landholdings in 1962. Tribal membership that year was slightly more than 600. The federal termination policy proved to have disastrous effects for all tribes that were terminated, and the Catawbas were no exception. They soon realized that termination had led to a weakened cultural identity and a decreased ability to maintain their community. As a result, the Catawba decided to fight their terminated status.

In 1973 the Catawba reorganized a tribal council, and the tribe was recognized by the state of South Carolina. In 1993, following a nearly 20-year court case, the Catawba regained their status as a federally recognized tribe and began the process of establishing a tribal roll. The Catawba Indian Nation tribal council administers a wide variety of programs, including social services and a very active cultural preservation program. In the early 2000s, approximately 2,200 Catawba Indians were living on reservation lands near Rock Hill, S.C. As of 2022, there were 3,300 enrolled members of the Catawba Nation. The Catawba Indian Nation is the only one of 573 federally recognized tribes in the United States to be located in the state of South Carolina.

References:

Catawba Indian Nation: https://www.catawba.com/about-the-nation

Brown, Douglas Summers. The Catawba Indians: The People of the River. 1966.

Hudson, Charles. The Catawba Nation. 1970.

Merrell, James H. The Indians' New World: Catawbas and Their Neighbors from European Contact through the Era of Removal. 1989.

Additional Resources:

Catawba Cultural Preservation: http://sites.google.com/site/catawbaculturalpreservation/

Hilton Pond Center. “The Catawba Indians: People of the River.” Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. http://www.hiltonpond.org/CatawbaIndiansMain.html.

North Carolina Digital Publishing Office. “The Papers of Arthur Dobbs: A Colonial Records Digital Edition.” MosaicNC.org. June 2023. https://mosaicnc.org/Arthur-Dobbs (accessed September 23, 2023).

University of South Carolina at Lancaster. Native American Studies Center. https://nativeamericanstudiescenter.godaddysites.com.

Image Credit:

"Map of the sites of the Cheraws and Catawbas. From Gregg's History of the Old Cheraws." Image courtesy of UNC, Documenting the American South. Available from https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/mcpherson/mcpherson.html#p197 (accessed May 22, 2012).

1 January 2006 | Moore, David G.