Fact and Fiction: Looking for the Lost Colonists

Roanoke Island

by Dr. Charles R. Ewen and Dr. E. Thomson Shields Jr.

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Fall 2007.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

The Roanoke Voyages

For many people, the story of England's attempts to set up a colony on Roanoke Island begins and ends with the 1587 Lost Colony—more than a hundred men, women, and children left on the island who were never heard from again. What those unfamiliar with the story don't realize is that there were actually three British colonies on Roanoke Island. They are all "lost" as far as archaeologists are concerned.

For many people, the story of England's attempts to set up a colony on Roanoke Island begins and ends with the 1587 Lost Colony—more than a hundred men, women, and children left on the island who were never heard from again. What those unfamiliar with the story don't realize is that there were actually three British colonies on Roanoke Island. They are all "lost" as far as archaeologists are concerned.

Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe explored the present-day Outer Banks of North Carolina on behalf of Sir Walter Raleigh for six weeks in 1584. Their accounts of what they found led Raleigh to dispatch Sir Richard Grenville the next year to further explore and begin settling the region. Grenville left 108 men under the command of Ralph Lane to establish a colony on Roanoke Island. These men were only too glad to be rescued by Sir Francis Drake when he happened by, after the next spring. Meanwhile, when Grenville returned in 1586 with supplies and more settlers, he found an empty encampment. He left behind a token force of fifteen men. No one knows exactly what happened to them, either. We know about these voyages from written records, but we have found little archaeological evidence, such as tools and everyday items—let alone building locations.

All of this set the stage for the appearance of the most famous to-be-lost colonists. John White returned to Roanoke in July 1587 as the leader of 117 settlers, including his pregnant daughter, Eleanor Dare, whose daughter Virginia in mid-August became the first English child born in the New World. (There was actually another pregnant woman in the colony, Margery Harvie, who had a baby shortly after Dare. She rarely gets mentioned because no one ever talks about second place.) The fact that the group arrived during one of the worst droughts in eastern North Carolina's history did not improve its chances for success. White soon headed back to England for supplies. Though he tried to return several times, nearly three years passed before he made it back to Roanoke. Like Grenville before him, White found a deserted encampment.

After that 1590 voyage, people have been looking for the Lost Colony since at least the 1607 Jamestown (Virginia) voyages, with no success. Still, the lure of the mystery has attracted archaeological investigations over the years. There has been little result.

Fort Raleigh

The first place in North Carolina that the English visited also was the first that archaeologists investigated. Talcott Williams mapped the Roanoke Island site in 1887 and began digging in 1895. The National Park Service picked up the hunt in 1947 and has continued on and off to this day, with little to show for the effort beyond the earthworks reconstructed and dubbed "Fort Raleigh."

The search for archaeological evidence of the 1580s expeditions kicked into higher gear with now-retired archaeologist Ivor Noël Hume in 1994. Hume found evidence of what he interpreted as a sixteenth-century science center near the rebuilt fort. He decided that everyone had been digging for the main settlement in the wrong place. The colonists had tested metal ores near the earthworks, he thought, but must have lived at another spot. Interested professionals formed the nonprofit First Colony Foundation to pursue these and other leads, with no success so far. However, hope springs eternal.

From History and Archaeology to Story

The question people ask most about the Roanoke voyages is what actually happened to the 1587 colonists. One idea is that they tried to go north to the Chesapeake Bay, where they originally meant to settle. Others have suggested sites along the Albemarle and Pamlico sounds that match White's statement that the colonists "were prepared to remove from Roanoke fifty miles into the main." Another line of thinking suggests that the English settlers intermingled with American Indians, perhaps moving inland eventually to become the Lumbee of Robeson County. Still others suggest variations on these ideas or other possible answers to the question of what happened to the Lost Colony.

The question people ask most about the Roanoke voyages is what actually happened to the 1587 colonists. One idea is that they tried to go north to the Chesapeake Bay, where they originally meant to settle. Others have suggested sites along the Albemarle and Pamlico sounds that match White's statement that the colonists "were prepared to remove from Roanoke fifty miles into the main." Another line of thinking suggests that the English settlers intermingled with American Indians, perhaps moving inland eventually to become the Lumbee of Robeson County. Still others suggest variations on these ideas or other possible answers to the question of what happened to the Lost Colony.

These ideas, at best, are hypotheses—educated guesses to explain events, but guesses that haven't been or cannot be tested. They are not theories—ideas that have been tested and shown to be highly probable—let alone facts. As hypotheses, they reveal as much about what we hope or believe as they do about what we know. For example, few people seem to assume that the colonists died from disease or hunger or were killed by any of the region's Indian tribes. Little Virginia especially avoids this ending in people's imaginations. Because we know so little about what happened to the colonists, their fate is ripe for storytelling. Countless books, an outdoor drama, a 1920s silent movie, and numerous television programs have taken up the tale.

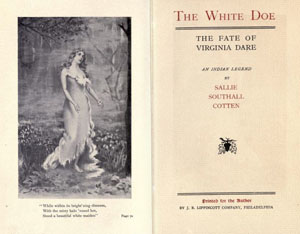

One example of these stories is that of the white doe. In 1901 Sallie Southall Cotten wrote a book-length poem entitled The White Doe: The Fate of Virginia Dare: An Indian Legend. Cotten told a story about Virginia surviving into adulthood, at which time two American Indians fought because they each wanted to marry her. One man was a magician. When Virginia said she wouldn't marry him, he turned her into a deer and tricked the other man into killing her during a hunt. Cotten's story, based on a fairy tale from Europe, adds elements of the Roanoke story and makes a few plot changes. Interestingly, people have retold her story as if it were actually Indian folklore. Today versions of the story can be found in books and on Web sites.

References and additional resources:

Hume, Ivor Noel. 1994. The Virginia adventure: Roanoke to James Towne. New York: Knopf.

NC LIVE resources about the Roanoke Colonies.

Powell, William Stevens, and Jay Mazzocchi. 2006. Encyclopedia of North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 982-983.

Resources in libraries [via WorldCat]

Roanoke Colonies Research Newsletter. Online in the NC Department of Cultural Resources Digital Collections.

Roanoke revisited. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/fora/forteachers/roanoke-revisited.htm

Quinn, David B. 1974. England and the discovery of America, 1481-1620, from the Bristol voyages of the fifteenth century to the Pilgrim settlement at Plymouth: the exploration, exploitation, and trial-and-error colonization of North America by the English. New York: Knopf.

Quinn, David B. 1955. The Roanoke voyages, 1584-1590; documents to illustrate the English voyages to North America under the patent granted to Walter Raleigh in 1584. Works issued by the Hakluyt Society, 2d ser., no. 104. London: Hakluyt Society.

Quinn, David B. 1985. Set fair for Roanoke: voyages and colonies, 1584-1606. Chapel Hill: Published for America's Four Hundredth Anniversary Committee by the University of North Carolina Press.

"Ships of the Roanoke Voyages." Fort Raleigh National Historical Site, National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/fora/forteachers/ships-of-the-roanoke-voyages.htm (accessed March 17, 2014).

Image credits:

Wickens, Jay. "Elizabeth II." Photograph. [n.d.]. NC ECHO, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources. (accessed March 17, 2014).

Cotten, Sallie Southall. 1901. The White Doe. Philadelphia : J. B. Lippincott company. https://archive.org/details/whitedoe00cottiala

1 January 2007 | Ewen, Charles R.; Shields, E. Thomson, Jr.

Listen to this entry

Listen to this entry