WWI: Life on the western front

American soldiers of World War I experienced a great deal of hardship while fighting on the western front in France and Belgium.

American soldiers of World War I experienced a great deal of hardship while fighting on the western front in France and Belgium.

Since air transportation was still a dream, America’s doughboys traveled on ships to France. These troop ships were often crowded and uncomfortable, with bunks stacked several layers high, and the men and their equipment forced into tiny spaces. The soldiers came up on deck only once or twice a day, usually for exercise or lifeboat drill. Many had never been to sea before, so they became sick from the pitching and rolling of the ship.

Troop ships sailed in convoys, groups of twenty-five or thirty vessels sailing in formation. They were protected by the American navy. The convoys constantly zigzagged across the water, making them difficult targets for German submarines. Athough there were sightings of submarines, only a few American troop ships were sunk during the war.

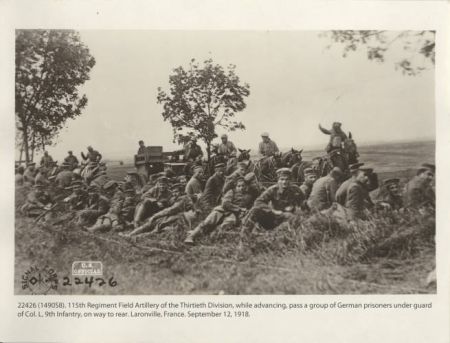

Almost all Americans arrived at French ports like Saint-Nazaire and Brest. However, the 30th Division, which had a large number of North Carolinians, was sent first to Britain. There the soldiers were given more training before going to France to join with the British army.

Most of the doughboys had time for training. The 81st Division, another unit with many North Carolinians, arrived in France in August 1918 but did not see combat until November. Experienced French and English instructors taught them about trench warfare at schools in the rear. Then the troops were sent to quiet sectors in the front lines to become familiar with conditions there.

No matter how realistic their training was, nothing could have prepared the Americans for the devastation of the western front. Four years of war had left the battlefront so churned up by shells and trenches that it looked like the surface of the moon. Poison gas had killed much of the vegetation. In Flanders, Belgium, where the 30th Division fought, the land was flat and low, and the trenches were often knee deep in water. When it was rainy, a wounded man might drown in the mud.

By 1918, the western front trenches ran in a four-hundred-mile line through France and Belgium from the North Sea to the Alps. Each set of trenches consisted of several lines: a main line and up to four lines behind it. The trenches were usually about four feet wide and about eight feet deep, but in some places they were much shallower. Soldiers reinforced the sides with sandbags, bundles of sticks or logs, or sheet metal.

By 1918, the western front trenches ran in a four-hundred-mile line through France and Belgium from the North Sea to the Alps. Each set of trenches consisted of several lines: a main line and up to four lines behind it. The trenches were usually about four feet wide and about eight feet deep, but in some places they were much shallower. Soldiers reinforced the sides with sandbags, bundles of sticks or logs, or sheet metal.

All trenches were dug in a zigzag pattern. The section facing the enemy line was known as a fire trench. The zigzags, intended to keep shell fragments from spreading very far, were called traverses. All along the line were strong points, sometimes built of concrete, where machine guns were placed.

Short trenches, or saps, extended about thirty feet toward the enemy line. These led to listening posts where sentries could listen for enemy troops sneaking up at night. All across the front, fifty feet of barbed wire entanglements protected the trench. The area between the Allied barbed wire and the enemy’s wire was known as no-man’s-land.

The line trenches were connected by zigzag communication trenches. Every night, small groups made the difficult journey along these trenches to the rear for supplies. The network of trenches could be very confusing, especially in the dark. For this reason, all trenches had names or numbers, and maps showed every intersection, fire trench, dugout, and wire belt.

The Germans had had four years to improve their trenches. By 1918, their line was made up of concrete-reinforced bunkers, often several stories below ground, with electric lights and elaborate barracks. Their positions had been chosen carefully, and they were defended by machine guns, barbed wire, and artillery.

The major problem for soldiers in the trenches was simple survival. Most hardly saw the enemy and spent their days repairing damage from shells or cave-ins, hauling food and water to the front, and carrying wounded men to the rear.

Food often arrived cold, and during artillery bombardments, it might not come for hours or days. Much of the time doughboys lived on the so-called Reserve Ration of hard bread, canned meat (usually corned beef, known to the men as Corned Willy), and instant coffee. The Army also developed an Emergency Ration, with a cake of powdered meat and wheat and one of chocolate. Each cake weighed about an ounce. The meat could be eaten dry, boiled into a gruel, or sliced and fried. The chocolate could be eaten dry or boiled into a hot drink. Both the coffee and the entire Emergency Ration were among the first successful attempts at making instant food.

The two most hideous parts of trench warfare were the rats and the bodies of dead soldiers. Rats were everywhere, spreading disease and feeding on food scraps and bodies. In many sectors of the front, the dead were buried in or near the trenches. Artillery blasts could dig up the bodies, then bury them again.

Every two weeks, usually at night, new units came up to the front lines through the communication trenches. They relieved those who had served on the line. The unit being relieved then had a week or two of rest in the rear. Usually, this “rest” involved a lot of labor.

The troops welcomed rest periods, even though they were never very far from the front lines. Rest camps were usually set up in deserted villages where doughboys used old stone barns or houses for shelter. Soldiers found the few villagers they did meet to be solid people who still supported the war even after they had lost nearly everything. The villagers and the Americans became friends. Also in the rear, the American Red Cross, the Knights of Columbus, the YMCA, and other organizations provided many of the little comforts that made life on the front easier.

The most important things the doughboy brought with him, more important than his training and his weapons, were his youth and confidence. The Americans were not as experienced as the Germans, but they made up for any lack with energy and enthusiasm. More than that, the time they spent in the trenches convinced them that the only way to win the war was to break out of the trenches and force the Germans into the open country beyond. There, the Germans could be defeated by superior American weapons and the strength of the young, confident doughboys.

At the time of this article’s publication, Les Jensen, author of a number of articles and books dealing with military history, served as a museum curator with the National Museum of the United States Army in Washington, D.C.

Educator Resources:

Grade 8: Trench Warfare in World War I. North Carolina Civic Education Consortium. http://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2012/05/TrenchwarefareinWWI.pdf

Additional resources:

North Carolinians and the Great War. Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries. https://docsouth.unc.edu/wwi/

Wildcats never quit: North Carolina in WWI. NC Department of Cultural Resources. http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/SHRAB/ar/exhibits/wwi/default.htm

"World War I." ANCHOR, A North Carolina History Online Resource. https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/world-war-i

WWI: NC Digital Collections. NC Department of Cultural Resources.

WWI: Old North State and the 'Kaiser Bill.' Online exhibit, State Archives of NC. http://www.history.ncdcr.gov/SHRAB/ar/exhibits/wwi/OldNorthState/index.htm

Image credits:

US Army, Signal Corps. 1918. "115th Regiment Field Artillery of the Thirtieth Division passing a group of German prisoners under guard of 9th Infantry, Laronville, France, September 12, 1918" State Archives of North Carolina.

https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/115th-regiment-field-artillery-of-the-thirtieth-division-passing-a-group-of-german-prisoners-under-guard-of-9th-infantry-laronville-france-september-12-1918/567110

"North Sea and the Alps." 2012. Map by Google.

1 May 1993 | Jensen, Les