Native American Settlement of North Carolina

by Stephen R. Claggett; Revised by SLNC Government and Heritage Library, July 2023

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Spring 1995.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

See also:

American Indians Part II - Before European Contact

American Indians at European Contact

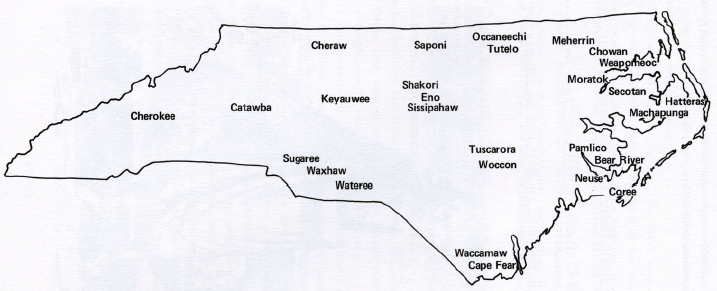

Over four hundred years ago, English colonists trying to settle on Roanoke Island encountered many Native Americans along the coast. At that time more than thirty Native American tribes were living in present-day North Carolina. They spoke languages derived from three language groups, the Siouan, Iroquoian, and Algonquian.

Over four hundred years ago, English colonists trying to settle on Roanoke Island encountered many Native Americans along the coast. At that time more than thirty Native American tribes were living in present-day North Carolina. They spoke languages derived from three language groups, the Siouan, Iroquoian, and Algonquian.

None of the prehistoric Native Americans who lived in North America had developed any sort of written language. They relied instead on oral traditions, such as storytelling, to keep records of their origins, myths, and histories. Our present knowledge of prehistoric inhabitants of this state depends on rare early historical accounts and, especially, on information gained through archaeology.

Prehistoric Native Americans

Archaeologists can trace the ancestry of Native Americans to at least twelve thousand years ago, to the time of the last Ice Age in the Pleistocene epoch. During the Ice Age, ocean levels dropped and revealed land that had previously been under the Bering Sea. Native American ancestors walked on that land from present-day Siberia to Alaska. Evidence suggests that their population grew rapidly and that they settled throughout Canada, the Great Plains, and the Eastern Woodlands, which included the North Carolina area. Archeological discoveries of human civilization in Monte Verde, Chile that dated 1,000 years prior to the Bering Strait migration called this theory into question. The Monte Verde discoveries also informed understandings that other prehistoric settlers could have traveled to the continent by boat. In fact, one of the oldest discoveries of early human settlement in the Americas is at Topper Site, South Carolina and is dated as being established 15,000 years ago.

The climate on the eastern seaboard was wetter and cooler twelve thousand years ago. Many species of animals roamed the forests and grasslands of our area, including now extinct examples of elephants (mastodons), wild horses, ground sloths, and giant bison. Other animals, now absent from the Southeast, included moose, caribou, elk, and porcupines.

Paleo-Indians, as archaeologists call those first people, hunted for these animals in groups using spears. They used the animals’ meat, skins, and remaining parts for food, clothing, and other needs. They also spent considerable time gathering wild plant foods and may have caught shellfish and fish. These first inhabitants of North Carolina were nomads, which means they moved frequently across the land in search of food and other resources.

Archaic people, like their ancestors, were nomads. They traveled widely on foot to gather food, to obtain raw materials for making tools or shelters, and to visit and trade with neighbors. Some Archaic people may have used watercraft, particularly canoes made by digging out the centers of trees.

These Archaic Indians did not have three things that are commonly associated with prehistoric Indians—bows and arrows, pottery, or an agricultural economy. In fact, the gradual introduction of these items and activities into North Carolina’s Archaic cultures marks the transition to the Woodland culture, which began around 2000 B.C.

Woodland Indians followed most of the subsistence practices of their Archaic ancestors. They hunted and fished and gathered food when deer, turkeys, shad, and acorns were plentiful. But they also began farming to make sure they had enough food for the winter and early spring months, when natural food sources were not available. They cleared fields and planted and harvested crops like sunflowers, squash, gourds, beans, and maize.

The Woodland Indians also developed bow-and-arrow technology. With a bow and arrow, Indians could hunt more efficiently, using single hunters instead of groups of hunters.

Archaeological evidence suggests that Woodland Indians were much more committed to settled village life than their ancestors had been. Though remains of their settlements can be found throughout North Carolina, these Indians tended to live in semi permanent villages in stream valleys.

Evidence also suggests that some Native Americans adopted religious and political ideas from a fourth major prehistoric culture, called Mississippian. Ancestral Cherokee Indian groups in the Mountains adopted some of the Mississippian ways. In prehistoric times, the so-called Pee Dee Indians were Mississippian Indians. The Pee Dee built a major regional center at Town Creek in present-day Montgomery County.

Mississippian Indians were more common in other parts of the Southeast and Midwest. They had a hierarchical society, with status determined by heredity or exploits in war. They were militarily aggressive and fought battles to gain and defend group prestige, territories, and favored trade and tribute networks. The surviving, often flamboyant artifacts from Mississippian Indian sites reflect the need that those individuals felt to show their status and glorify themselves.

Measuring the involvement of historic North Carolina Indians with those large, powerful Mississippian groups is very difficult. Some minor elements of Mississippian culture can be found in various parts of our state, particularly in pottery types or religious or political ornaments. The Algonquian-speaking Indians met by the Roanoke Island colonists reflected some Mississippian influence, as did the later Cherokee.

Measuring the involvement of historic North Carolina Indians with those large, powerful Mississippian groups is very difficult. Some minor elements of Mississippian culture can be found in various parts of our state, particularly in pottery types or religious or political ornaments. The Algonquian-speaking Indians met by the Roanoke Island colonists reflected some Mississippian influence, as did the later Cherokee.

Historic Native Americans

Most of the Indian groups met by early European explorers were practicing economic and settlement patterns of the Woodland culture. They grew crops of maize, tobacco, beans, and squash, spent considerable time hunting and fishing, and lived in small villages. In 1550, before the arrival of the first permanent European settlers, more than one hundred thousand Native Americans were living in present-day North Carolina. By 1800 that number had fallen to about twenty thousand.

What happened to the Native Americans? Unlike Europeans, Native Americans had no resistance, or immunity, to diseases that the Europeans brought with them. These diseases, such as smallpox, measles, and influenza, killed thousands of natives throughout the state.

Settlement by European Americans also pushed many Native Americans off their land. Some made treaties with the Whites, giving up land and moving farther west. Others fought back in battle but lost and were forced to give up their lands. These battles, as well as war with other Native American tribes, also killed many.

The fates of the three largest Native American tribes—the Tuscarora, the Catawba, and the Cherokee—are examples of the fates of the other tribes in North Carolina.

Tuscarora

In the Coastal Plain Region, most of the smaller Algonquian-speaking tribes moved westward in the face of growing numbers of white settlers. But the Iroquoian-speaking Tuscarora stayed, living in villages along the Pamlico and Neuse Rivers.

Tensions between White settlers and the Tuscarora increased as White settlements in the Coastal Plain grew. European settlers would not let the Tuscarora hunt near their farms, which reduced the Tuscarora’s hunting lands. Some White traders cheated the Tuscarora. Some settlers even captured and sold Tuscarora into slavery.

The settlement of New Bern in 1710 took up even more of the Tuscarora land and may have provoked the Tuscarora Indian War (1711–1714). In 1711 the Tuscarora attacked White settlements along the Neuse and Pamlico Rivers. They were defeated in 1712 by an army led by Colonel John Barnwell of South Carolina. Later in 1712 the Tuscarora agreed to a peace treaty. According to terms in that treaty they were to move out of the area between the Neuse and Cape Fear Rivers.

After this peace, the North Carolina Assembly refused to reward Barnwell and his South Carolina troops. The Assembly felt the army had not completely destroyed the Tuscarora’s power. As a result, while returning to South Carolina, Barnwell’s troops killed some Tuscarora, captured about two hundred Tuscarora women and children, and sold them into slavery for the money. The Tuscarora retaliated by attacking more towns. The Tuscarora were defeated in a 1713 battle at Fort Noherooka (in present-day Greene County). Up to one thousand four hundred Tuscarora had been killed in the war. Another one thousand had been captured and sold into slavery. Many of the surviving Tuscarora left North Carolina and settled in New York and Canada.

Catawba

In the Piedmont Region, the Siouan-speaking Catawba Indians were friendly to the settlers. But disease, especially smallpox, killed many. War with neighboring tribes also reduced their number. Of the five thousand Catawba estimated to have been living in the Carolinas in the early 1600s, fewer than three hundred remained in 1784.

Cherokee

In the Mountain Region lived the Cherokee. At the start of the French and Indian War (1754–1763), they joined the British and the colonists in fighting the French. But when some Cherokee were killed by Virginia settlers, the Cherokee began attacking White settlements along the Yadkin and Catawba Rivers. They were defeated and made peace in 1761.

In return for this peace, the British promised that no White settlements would be allowed west of the Appalachian Mountains. But land-hungry Whites ignored this promise and continued to settle on Cherokee land.

During the American Revolution (1775–1783), the Cherokee sided with the British. They thought that if the British won, the British government would protect their land from further settlement. They also hoped to gain back some of the lands they had lost to the Whites. During the war, Cherokee and Creek Indians attacked White settlements. Colonists sent troops that defeated the Indians. In a 1777 treaty, the Cherokee gave up all lands east of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

During the American Revolution (1775–1783), the Cherokee sided with the British. They thought that if the British won, the British government would protect their land from further settlement. They also hoped to gain back some of the lands they had lost to the Whites. During the war, Cherokee and Creek Indians attacked White settlements. Colonists sent troops that defeated the Indians. In a 1777 treaty, the Cherokee gave up all lands east of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Conflicts continued into the 1790s. A 1792 treaty created a boundary between Cherokee and White settlers. The United States government promised to protect the Cherokee land from further settlement. But as White settlement continued, the federal government began thinking about removing the Cherokee and other Native Americans living east of the Mississippi River. In 1838 President Martin Van Buren acted on a policy established earlier by Andrew Jackson and sent federal troops to forcibly remove the Cherokee to the newly established Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma. About twenty thousand Cherokee were forced to leave. The path they took has been called the Trail of Tears because so many died on this journey west.

Some Cherokee avoided the troops and stayed behind in North Carolina. They joined the Oconaluftee Cherokee Indians, who, because of an 1819 treaty, were allowed to stay in North Carolina. Together, their descendants make up the Eastern Band of the Cherokee and now live in the Qualla Boundary, a reservation in five different counties in western North Carolina. Several other modern Native American groups, such as the Lumbee, the Haliwa-Saponi, and the Coharie, live in North Carolina. They are direct descendants of prehistoric and early historic inhabitants.

Additional references and resources:

Catawba College. Mapping 'Murican History. [collection of static and interactive maps and links to resources]. http://faculty.catawba.edu/cmcallis/history/mapping/america.htm (accessed January 26, 2016).

Excavating Occaneechi Town: An archaeology primer. LEARN NC. http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/occaneechi-archaeology-primer/?ref=search

Intrigue of the past: North Carolina's first peoples. Teacher's activity guide. http://www.rla.unc.edu/lessons/Menu/title.htm

Montaigne, Fen. “The Fertile Shore.” Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Institution, January 2020. Accessed July 3, 2023 at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/how-humans-came-to-americas-180973739/.

National Archives (United Kingdom). What was early contact like between Europeans and Natives? http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/lesson37.htm

NC Commission of Indian Affairs, North Carolina Indians. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/organic-certification-for-field-crops-a-guide/3280882?item=32918677

NC Office of State Archaeology. Online reports and summaries. http://www.archaeology.ncdcr.gov/ncarch/articles/articles.htm

“Other Migration Theories.” National Parks Service, February 22, 2017. Accessed July 3, 2023 at https://www.nps.gov/bela/learn/historyculture/other-migration-theories.htm.

Research Laboratories of Archaeology. Archaeology of North Carolina. http://rla.unc.edu/ArchaeoNC/index.htm

Research Laboratories of Archaeology. Video clips. http://www.rla.unc.edu/video/index.html

UNC-Chapel Hill. Picturing the New World: The hand-colored De Bry engravings of 1590. http://www.lib.unc.edu/dc/debry/

Image credits:

DeBry, Theodore, Native Americans around a fire. 1590. UNC-Chapel Hill. Picturing the New World: The hand-colored De Bry engravings of 1590. http://dc.lib.unc.edu/u?/debry,49

“Mother and child in papoose on Qualla Boundary,” 1941. Photograph no. ConDev4005B. From the North Carolina Conservation and Development Department, Travel and Tourism Division Photo Files, North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC, USA. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/mother-and-child-in-papoose-on-qualla-boundary./343970

NC Commission of Indian Affairs, Fig. 1. North Carolina Indian Tribes at the Time of European Contact. From North Carolina Indians. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/north-carolina-indians/2308925?item=2316481

1 January 1995 | Claggett, Stephen R.

Listen to this entry

Listen to this entry