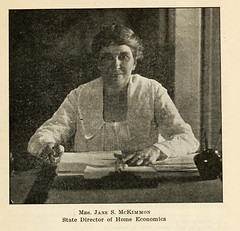

Jane S. McKimmon

by Louise Benner

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian, Spring 2007.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

Related Entries: Women; Agriculture & the Great Depression

In 1945 Jane Simpson McKimmon wrote a book called When We’re Green We Grow. The book told the story of McKimmon’s career as leader of North Carolina’s home demonstration agents, who traveled the state teaching homemaking skills to farm women. When McKimmon began her work in 1911, she was one of only five agents in the entire United States. She was a pioneer in a new career for women: home economics. Home economists use science to improve home and family life.

Jane Simpson was born in Raleigh in 1867. She graduated from Peace Institute (now Peace College) at age sixteen. At age eighteen she married Charles McKimmon. The McKimmons lived in Raleigh, but even through the mid-1940s, most North Carolinians lived on farms. Farm families usually occupied drafty houses with no electricity, no indoor bathrooms, no running water, no heat except from a fireplace or woodstove, and no evening light other than what kerosene lamps might provide. Endless chores for children included chopping wood, getting water from the well, pulling weeds, taking care of livestock, and preparing and cooking food. Other than a few things like sugar, coffee, and salt, a family’s food came from the farm. Rural areas had no supermarkets, only small neighborhood stores.

Jane McKimmon, interested in improving the lives of farm families, became a speaker for the Farmers’ Institute, a group that shared agricultural research with the public. She traveled the state talking to women about preparing food. Her specialty was bread making. McKimmon not only talked about baking bread; she showed audiences how to do it and helped them better use their equipment. For instance, at that time, wood usually heated the ovens in farm households. To check the temperature, agents told women to place a piece of white paper in the oven for one minute. If the paper burned or turned really brown, the oven was too hot. Audience members could see and taste breads made using McKimmon’s methods. They remembered these demonstrations better than words alone.

When the federal government began to set up programs to help farmers grow larger and better crops, some efforts targeted young people. In Ahoskie in 1909, I. O. Schaub—the first appointed farm extension agent for any state—started Corn Clubs for boys. Members received one-acre plots of land, learned new farming methods, and kept the profits from their crop. Many Corn Club boys doubled, tripled, and even quadrupled plot yield. Girls who saw their brothers making money and enjoying the process wanted to participate. A few girls were allowed into Corn Clubs, but growing corn was not considered suitable for girls.

Schaub was a neighbor of the McKimmons in Raleigh and knew about Jane McKimmon’s work with the Farmers’ Institute. He recommended that she head North Carolina’s program for girls, and she became the state’s first woman home demonstration agent. The program was based within the Agricultural Extension Service at North Carolina State College, now the Cooperative Extension Service at North Carolina State University.

Leaders decided that tomato growing and canning were suitable for schoolgirls. In 1911 canning—preserving food in sterilized jars or cans—was new on many farms. Girls got the chance to grow tomatoes on one-tenth-acre plots. Tomato Clubs grew tomatoes and then canned them, using safe and sanitary methods learned from home demonstration agents. Club members could sell their canned tomatoes at local curb markets.

Tomato Clubs nationwide adopted the name 4-H. Each H marked in the 4-H clover symbol stood for an ideal of the organization: head, heart, hands, and health. The 4-H clubs expanded their interests to anything that made farm life more productive and pleasant. Except on the state level, boys and girls had separate activities until after 1945. Before racial segregation in all clubs ended in 1964, separate clubs existed for black and white members.

When McKimmon started her work, the cash crops of cotton and tobacco made up the biggest part of most farmers’ incomes. After expenses, money proved scarce. The standard for a good year was having enough to eat so that no family member went hungry. In theory, men did the fieldwork, and women managed the household. Few farms, though, could survive without women and children working in the fields. Married women had no time to help by getting paying jobs, and most Americans at the time believed that the business world should be left to men.

Girls learned to cook when they were young, to free their mothers for other work. But few mothers or daughters understood nutritional needs, food conservation, or ways to best use their time in the kitchen. A lot of canned food spoiled before being eaten. Cooking was seasonal and relied too much on a “ham and hominy” diet. Milk was often given to calves rather than children, and vegetables were cooked for a long time, destroying vitamins. No one knew much about vitamins anyway. Many children suffered from decayed teeth and a bone-softening disease called rickets because of poor diets.

Food shortages during World War I brought requests for more gardening and canning information. People wanted to know how to preserve the food they grew. Community canneries were a new idea, and 132 operated in the state during 1917–1918. McKimmon was appointed to the State Food Administration to help increase food production and conserve for the war effort.

Food shortages during World War I brought requests for more gardening and canning information. People wanted to know how to preserve the food they grew. Community canneries were a new idea, and 132 operated in the state during 1917–1918. McKimmon was appointed to the State Food Administration to help increase food production and conserve for the war effort.

In the 1920s home demonstration agents organized women’s Saturday markets to sell home-produced food. McKimmon said, “It was an unheard-of thing before the market was organized to see a farm woman paid for hours spent in work, no matter how long they were nor what they involved.” Agents taught safe canning methods and frozen food preparation before many people had home freezers. Families could rent drawer space for foods prepared at home in freezer locker plants in county seats.

The Great Depression of the 1930s brought lean years to North Carolina. People lost jobs, and prices for cotton and tobacco fell. Farmers had depended on making money from the cash crops, and those who had trouble selling their crops could not afford to buy supplies or food. Leaders set up a state Office of Relief. McKimmon worked with its director to get food, fuel, and clothing to farm families in need. Families short of money tried to barter what they had for what they needed. Some started home industries based on what was available, such as growing cucumbers and selling pickles made from them. More people joined home demonstration classes and 4-H hoping to learn ways to earn money at home.

Despite the Depression, 4-H members in the 1930s enjoyed special opportunities. Members nominated by their county agent might go to Raleigh for a week of classes and fun, staying in college dorms. Classes included the latest food preservation methods, the newest sewing techniques, modern home decorating, and even landscaping. McKimmon—greatly respected as the “queen” of Home Demonstration—would speak.

Although McKimmon resigned her position as state home demonstration agent in 1937, she continued to work throughout World War II and was a member of the State Council of National Defense. She led the extension service’s work with families and 4-H clubs to increase food production for the war effort.

McKimmon, who died in 1957, received an honorary doctorate from the University of North Carolina. In 1949, when few people had television, NBC dramatized her life in a coast-to-coast radio broadcast. Officials at North Carolina State University named the McKimmon Center for Extension and Continuing Education for her, in recognition of her support for continuing education. She insisted that her agents attend college and earned two advanced degrees after she was fifty years old. McKimmon and Ruth Current—who succeeded her as state home demonstration agent—remain two of three women among the thirty-one people elected to the North Carolina Agricultural Hall of Fame.

During McKimmon’s first year of promoting better living conditions, 416 farm girls from fourteen North Carolina counties enrolled in 4-H clubs. After thirty years under her leadership, there were 75,000 girls enrolled from all one hundred counties. McKimmon said she worked with “people who were green and ready to grow; and I have seen the sap rise, the leaves put forth, and a multitude of blossoms bring fruit in its season.” North Carolina has changed from a rural to an urban economy, but in 2007 there are still 208,000 4-H members who inherit McKimmon’s legacy.

At the time of this article’s publication, Louise Benner was working as a curator of costume and textiles at the North Carolina Museum of History.

Additional Resources:

LearnNC, 4-H and Home Demonstration Work During World War II: https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/4-h-and-home-demonstration.

NC State University, McKimmon Center History: https://onece.ncsu.edu/mckimmon/divisionUnits/mcece/ourHistory.jsp

Image and Video Credits:

North Carolina 4-H: North Carolina 4-H History. Located at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rrt86iUQJqg. Accessed March 6, 2012.

North Carolina Agricultural Society. "North Carolina State Fair Premium List 1921." Photograph. Government & Heritage Library on Flickr. Sept. 26, 2011. Accessed Mar. 20, 2024. https://www.flickr.com/photos/statelibrarync/6186193178/.

Jay Seymour Studios. "Academy Award winning actress Jane Darwell (left) and Home Demonstration pioneer Jane McKimmon." North Carolina State University Libraries Special Collections Research Center. 1949. Accessed Mar. 20, 2024 at https://d.lib.ncsu.edu/collections/catalog/0000546.

"Home demonstration Christmas party, including Jane McKimmon, Virginia Wilson, and Ruth Current, Dec. 1947." North Carolina State University Libraries Special Collections Research Center. Dec. 1947. Accessed Mar. 20, 2024 at https://d.lib.ncsu.edu/collections/catalog/0000486.

1 January 2007 | Benner, Louise