Provided by North Carolina State University, D. H. Hill Library and Special Collections

North Carolina State University was founded within the context of rapid advances in late nineteenth-century American higher education. Two economic interest groups strongly supported the founding of an agricultural and technical school in the state. The Watauga Club, a group of businessmen, looked to higher education to develop the state's industrial and manufacturing economy. Several farmers' organizations also believed that education could bolster the state's traditional economic resources in agriculture.

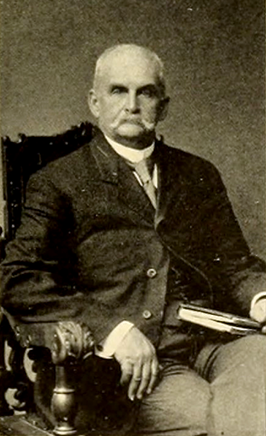

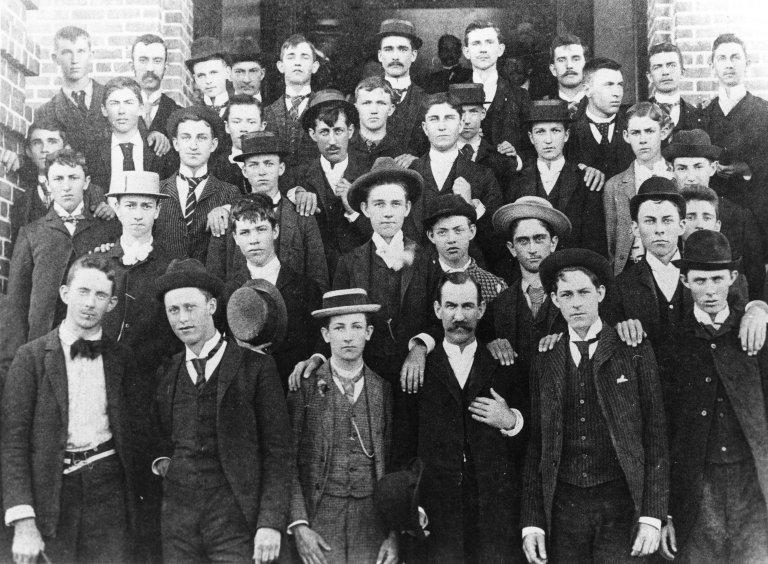

Because of the advocacy of these two groups, in 1887 the North Carolina General Assembly created the North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts as the state's land-grant institution to provide teaching, research and extension services to the people of the state. The College officially opened its doors in 1889, with Alexander Holladay as the first President. Classes began that fall with seventy-two students, six faculty, and one building – Main Building, now Holladay Hall. Two general fields of study were available, agriculture and mechanics, with a third in applied science added in 1893. Coursework in military science was added in 1894, and all students were compelled to participate in military drills each week. By the turn of the century, the college had grown to 300 students and six buildings, and had diversified its curricula with more specialization offered in agricultural and mechanical coursework. The college’s first decade ended with a new President, as George Tayloe Winston succeeded the retiring Holladay.

From the start, the school’s research mandate was confirmed as the work of the North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station were transferred to the college, to be jointly run with the state Department of Agriculture. To that end, a test farm was established at the western fringe of campus, and the college shared its research facilities with the work of the Station. Problems arose quickly, however, as the state Department of Agriculture resented having to work with the new college, and work at the Station was constantly plagued with jealousies and institutional rivalries. Not until 1926 and the decade following would the majority of these inter-institutional problems be resolved. In the meantime, however, the Station often produced a high caliber of work which was of invaluable assistance to farmers and industry across the state.

Extension and outreach work at State College received major boosts in 1909 and 1914, thanks to two federal programs. The first occurred when State College signed the first memorandum of understanding with the United State Department of Agriculture for cooperative demonstration work in the country. This agreement provided for the creation of Boys’ and Girls’ Clubs in 1909, which in turn became the 4-H program in 1926. The second took place in 1914, with the passage of the Smith-Lever Act, land grant colleges were enabled to establish state, county, and local extension programs to further support their existing demonstration work. North Carolina did so by establishing the Cooperative Agricultural Extension Service later that year at State College.

By 1917, the school’s teaching, research, and extension activities were broad enough that the Board of Trustees agreed to a name change: North Carolina State College of Agriculture and Engineering, thereby officially adopting the “State College” colloquialism that had been in use for years. Another significant development occurred that year when the College’s agricultural curricula were combined into a School of Agriculture, administered by a new Dean of Agriculture. Despite this change, by the early 1920s College leaders realized that further changes were needed in the academic administration. To assist in making their decisions, President Wallace Riddick called in U.S. Bureau of Education specialist George Zook to undertake a survey of the College administration.

Zook’s report suggested a number of major changes needed to be made to the administration of the College, and many of his recommendations were implemented in 1924. The most significant of the changes concerned the creation of three new schools: a School of Engineering, a School of Science and Business, and a revised School of Agriculture. Each school was to be headed by an administrative dean, who would in turn report to the President, thus freeing him from many of the day-to-day academic tasks of the College. Further reorganization was undertaken later in the decade, with the creation of the Graduate School and the Schools of Textiles and Education.

The effects of the Depression brought about the next major changes to the State College landscape. Economic hardship and a lack of funds threatened to undermine the advances of the 1920s, until sweeping education reforms were passed by the state legislature. The result was the Consolidated University of North Carolina, wherein three state universities – UNC at Chapel Hill, the Women’s College at Greensboro, and State College in Raleigh – were combined administratively in order to combat inefficiency and redundancy in public higher education. For State College, this meant several things. First, the School of Science and Business was abolished, and its departments either shuffled into another School or eliminated. Second, the School of Education was downgraded to department status. Finally, the College underwent another name change, this time to North Carolina State College of Agriculture and Engineering of the University of North Carolina. The Consolidated University arrangement existed until 1971, when it was superseded by the sixteen-campus University of North Carolina system, still in place today.

As the Depression slowly receded, North Carolina State College renewed its growth and development. Enrollment reached new heights, passing the 2,000 mark in 1937, and many of the school’s programs saw significant growth, particularly in extension and engineering. World War II and its aftermath, however, wrought more drastic changes to the academic and physical landscape at State College. Enrollment during wartime suffered greatly, dropping below one thousand students by 1943, and many academic programs were greatly curtailed. Despite these difficulties, the College did make contributions to the war effort, hosting a number of military detachments and training exercises, and refitting the work of several departments and programs to military and defense purposes. One example of this effort was the Navy diesel program, whereby staff in the Mechanical Engineering Department trained Navy personnel in the operation of diesel engines. Through the course of the war over 1,500 men were trained via this effort. Considering all the programs offered during the war, State College trained over 23,000 men and women for the war effort.

Faced with many challenges during the postwar years, State College experienced growth unparalleled in its history during this time. The G.I. Bill brought thousands of ex-servicemen to campus, and enrollment shot past the 5,000 mark in 1947. The College struggled to provide academic and residential space for its new students, and temporary structures were built to meet the demand. Pre-fab housing and trailers were constructed at the Vetville, Westhaven, and Trailwood sites on campus, and numerous abandoned barracks and Quonset huts were moved or built to temporarily house some academic programs. Major new programs were also created, including the School of Architecture and Landscape Design in 1947 (renamed as the School of Design in 1948), the School of Education in 1948, and the School of Forestry in 1950.

Although the 1950s generally represented a time of quiet growth and reorganization, several significant changes did occur during that time. Academically, several programs achieved national recognition, including work in agriculture, engineering, and design. Notably, the cooperative agricultural project with USAID and the government in Peru was established in 1954. The College also saw major building projects, with over a dozen newly constructed buildings appearing on campus. Most significantly, and a change that occurred with relatively little fanfare, was the admission of the first African-American students to State College, in 1953 (graduate) and 1956 (undergraduate).

Academic programs continued expanding at State, with the creation of the School of Physical Science and Mathematics in 1960, and the establishment of a B.A. degree for the School of Liberal Arts (renamed the School of Humanities and Social Sciences in 1977). Single-year enrollment reached 10,000 in 1966. In addition, the long-standing military tradition at the University was scaled back when, beginning with the 1965 school year, compulsory ROTC for all students was abolished.

The institution also faced the same turmoils during the sixties and seventies that confronted larger American society, but perhaps the most turbulent on-campus imbroglio was that over the institution’s latest name change, which began in 1962. State College officials desired to change the institution’s name to North Carolina State University. When Consolidated University administrators approved a change to the University of North Carolina at Raleigh, many were outraged. Protests and letter-writing campaigns sought relief from this proposal, and finally in 1963 a compromise was reached, with State College officially becoming North Carolina State of the University of North Carolina at Raleigh. Students, faculty, and alumni continued to express dissatisfaction with this name, however, and after two more years of political wrangling, the name was once again changed, this time to the current North Carolina State University at Raleigh.

Change was in the works once again, as the University celebrated its 100th anniversary in 1987. Reflecting trends at peer universities, eight of the Schools at the University were redesignated as Colleges, in order to administrate them more efficiently. That same year brought another milestone, when the state government transferred over 700 acres of land to the University to become a new Centennial Campus, housing research, residential, and corporate facilities. Designed not to replace but to supplement the original campus, Centennial Campus has become a cornerstone of the University, blending traditional academic research and teaching, government and corporate interests, and residential living into an innovative and dynamic community.

Known as the "People's University," North Carolina State University has developed into a vital educational and economic resource, and a wealth of university outreach and extension programs provide services and education to all sectors of the state's economy and its citizens. With a student body of nearly 30,000, nearly two thousand faculty, and research and program expenditures over $440 million, the University is an active and vital part of North Carolina life.