Louisa Jacobs was an author, abolitionist and activist who was born into slavery. Her mother, Harriet Jacobs, was also an author, abolitionist, and activist, born into slavery in Edenton, North Carolina, but is perhaps best known for her narrative that details her life and escape from slavery, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.

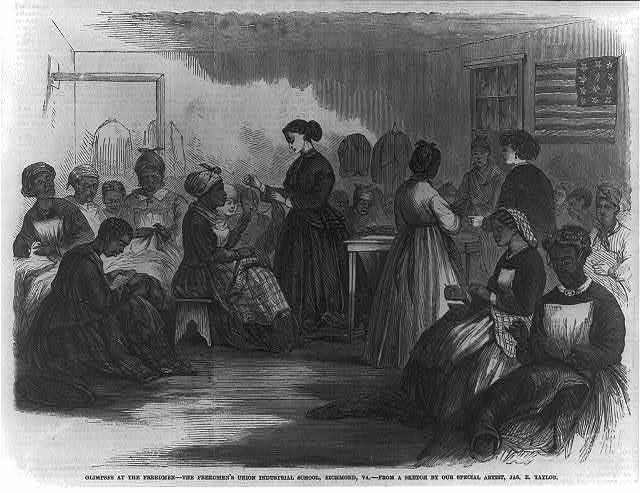

Louisa and her mother moved to Washington D.C. in 1862 to assist former slaves who had become refugees during the war. In 1863, the two women founded a school in Alexandria, Virginia. Louisa and Harriet left Alexandria at the end of the Civil War and moved south to Savannah, Georgia, where they continued their efforts to educate former slaves.

Below is an 1866 report by Louisa Jacobs regarding her and mother's work to educate freed people in Savannah, Georgia. In the report she discusses not only events and experiences related to the school, but also the adversity and exploitation faced by the freed people in the community.

I wish you could look in upon my school of one hundred and thirty scholars. There are bright faces among them bent over puzzling books: a, b, and p are all one now. But these small perplexities will soon be conquered, and the conqueror, perhaps, feel as grand as a promising scholar of mine, who had no sooner mastered his A B C's, when he conceived that he was persecuted on account of his knowledge. He preferred charges against the children for ill-treatment, concluding with the emphatic assurance that he knew a "little something now."

I have called mine the Lincoln School.

We learn from the record kept at the Freedmen's Bureau, that there are two thousand two hundred children here. Some six or seven hundred are yet out of school. The freedmen are interested in the education of their children. You will find a few who have to learn and appreciate what will be its advantage to them and theirs. The old spirit of the system, "I am the master and you are the slave," is not dead in Georgia. For instance, the people who live next door owned slaves. They are as poor as that renowned church mouse, yet they must have their servant. Employer and employed can never agree: the consequence is a new servant each week. The last comer had the look and air of one not easily crushed by circumstances. In the course of a few days, the neighbors were attracted to their doors by the loud voice of the would-be slaveholders. Out in the yard stood the mistress and her woman. The former had struck the latter. I am no pugilist, but, as I looked at the black woman's fiery eye, her quivering form, and heard her dare her assailant to strike again, I was proud of her metal. In a short time the husband of the white woman made his appearance, and was about to deal a second blow, when she drew back telling him that she was no man's slave; that she was as free as he, and would take the law upon his wife for striking her. He blustered, but there he stood deprived of his old power to kill her if it had so pleased him. He ordered her to leave his premises immediately, telling her he should not pay her a cent for the time she had been with them. She quietly replied that she would see about that. She went to the Bureau, and very soon had things made right.

In this beautiful Forest City,—for it is beautiful notwithstanding the curse that so long hung over it,—there is a street where colored people were allowed to walk only on one side. Not long since an acquaintance of mine, while walking on what had been the forbidden side, was rudely pushed off by a white man, and told that she had no right there. She gave him to understand that Sherman's march had made Bull Street as much hers as his. Veils were not allowed to be worn by colored women. After the army came in, they went out with two on,—one over the face, the other on the back of the bonnet. Many of the planters have returned to their homes. Some wish to make contracts with their former slaves; but the majority are so unfair in their propositions, that the people mistrust them.

Here is but one instance. A Mr. H—— has brought with him his old overseer. The master was noted for cruelty. For the slightest offence, he would cause his slaves to be stripped and whipped, while he would walk up and down, indulging in coarse jokes. After a hundred lashes had been given, he would say to the foreman, "Look out, there! you are not doing your duty." On which the man would take off his jacket, and say to the poor victim, "De Lord hab mercy on you now. I'se 'blige to do it."

This man proposes to make contracts on these conditions: a boat, a mule, pigs and chickens, are prohibited; produce of any kind not allowed to be raised; permission must be asked to go off of the place; a visit from a friend punished with a fine of $1.00, and the second offence breaks the contract. Is this freedom, or encouragement to labor? Those who have had a taste of freedom will not make contracts with such men. Are they to be blamed, and held up as vagrants too lazy to earn a living?

Others will not hire men who are unwilling to have their wives work in the rice swamps. There is no limit to the injustice daily practised on these people. There were some here, this week, who never knew they were free, until New-Year's Day, 1866. They had been carried into the interior of South Carolina. Now they are brought and driven back into the State: out of one Egypt into anotherThis references was to the Biblical story of Moses, who led the Hebrews out of Egypt, where they had been enslaved.. They are looking for "de freedom," they say. God grant they may find it! Mother, in her visits to the plantations, has found extreme destitution. We were told to-day, by Mr. Simms, the freedmen's faithful friend and adviser, that the owners of two of the plantations under his charge have returned, and the people are about to be sent offMany formerly enslaved people took over plantations that had been deserted by their masters. Former slaves believed that the land also belonged to them because they had worked and lived on these plantations. Legally, though, the plantations were not theirs, and when the plantation owners returned, many slaves were were forced to leave. Others simply abandoned the plantation, fearing that their former masters would treat them unfairly or abuse them..

There are eight freedmen's schools here; the largest has three hundred scholars. The teachers of the two largest schools are colored; most of them natives of this place. These schools have been partially supported by the colored people, and will hereafter be entirely so.

Source Citation:

Jacobs, Louisa. "From Savannah." The Freedmen's Record, March 1866.

Published online by Documenting the American South. University Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/jacobs/support14.html