The Albany Plan of Union was a plan to place the British North American colonies under a more centralized government. The plan was adopted on July 10, 1754, by representatives from seven of the British North American colonies. Although never carried out, it was the first important plan to conceive of the colonies as a collective whole united under one government.

Representatives of the colonial governments adopted the Albany Plan during a larger meeting known as the Albany Congress. The British government in London had ordered the colonial governments to meet in 1754, initially because of a breakdown in negotiations between the colony of New York and the Mohawk nation, part of the Iroquois Confederation. More generally, imperial officials wanted to sign a treaty with the Iroquois that would articulate a clear colonial-Indian relations policy for all the colonies to follow. The colonial governments of Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts and New Hampshire all sent commissioners to the Congress. Although the treaty with the Iroquois was the main purpose of the Congress, the delegates also met to discuss intercolonial cooperation on other matters. With the French and Indian War looming, the need for cooperation was urgent, especially for colonies likely to come under attack or invasion.

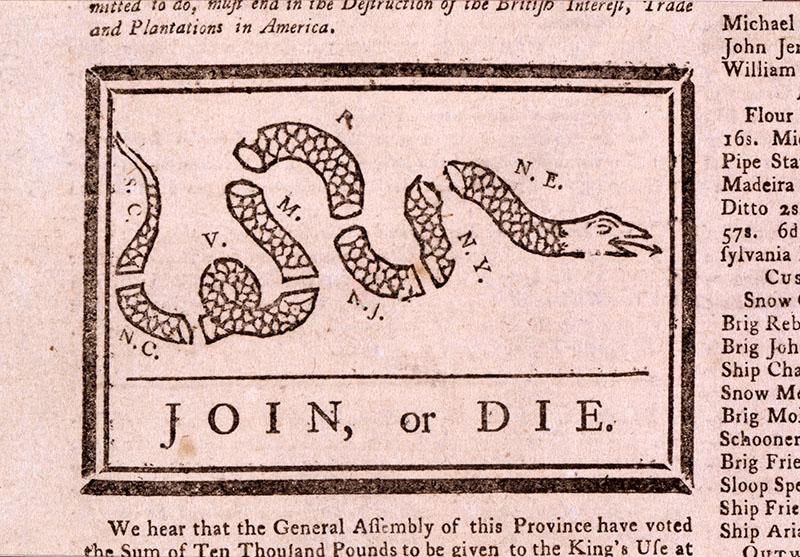

Prior to the Albany Congress, a number of intellectuals and government officials had formulated and published several tentative plans for centralizing the colonial governments of North America. Imperial officials saw the advantages of bringing the colonies under closer authority and supervision, while colonists saw the need to organize and defend common interests. One figure of emerging prominence among this group was Pennsylvanian Benjamin Franklin. Earlier, Franklin had written to friends and colleagues proposing a plan of voluntary union for the colonies. Upon hearing of the Albany Congress, his newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette, published the political cartoon “Join or Die,” which illustrated the importance of union by comparing the colonies to pieces of a snake’s body. The Pennsylvania government appointed Franklin as a commissioner to the Congress, and on his way, Franklin wrote to several New York commissioners outlining “short hints towards a scheme for uniting the Northern Colonies” by means of an act of the British Parliament.

The Albany Congress began on June 19, and the commissioners voted unanimously to discuss the possibility of union on June 24. The union committee submitted a draft of the plan on June 28, and commissioners debated aspects of it until they adopted a final version on July 10.

Although only seven colonies sent commissioners, the plan proposed the union of all the British colonies except for Georgia and Delaware. The colonial governments were to select members of a “Grand Council,” while the British Government would appoint a “president General.” Together, these two branches of the unified government would regulate colonial-Indian relations and also resolve territorial disputes between the colonies. Acknowledging the tendency of royal colonial governors to override colonial legislatures and pursue unpopular policies, the Albany Plan gave the Grand Council greater relative authority. The plan also allowed the new government to levy taxes for its own support.

Despite the support of many colonial leaders, the plan, as formulated at Albany, did not become a reality. Colonial governments, sensing that it would curb their own authority and territorial rights, either rejected the plan or chose not to act on it at all. The British Government had already dispatched General Edward Braddock as military commander in chief along with two commissioners to handle Indian relations, and believed that directives from London would suffice in the management of colonial affairs.

The Albany Plan was not conceived out of a desire to secure independence from Great Britain. Many colonial commissioners actually wished to increase imperial authority in the colonies. Its framers saw it instead as a means to reform colonial-imperial relations, while recognizing that the colonies collectively shared certain common interests. However, the colonial governments’ own fears of losing power, territory, and commerce at one another’s expense, and at the expense of the British Parliament, ensured the Albany Plan’s failure.

Despite the failure of the Albany Plan, it served as a possible model for future attempts at union: it attempted to establish the division between the executive and legislative branches of government, while establishing a common governmental authority to deal with external relations. More importantly, it conceived of the colonies of mainland North America as a collective unit, separate from the mother country but also from the other British colonies in the West Indies and elsewhere.

Source Citation:

"Albany Plan of Union, 1754." n.d. Office of the Historian. U.S. Department of State. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1750-1775/albany-plan