Introduction

The Civil War had the highest number of deaths and wounds of any war fought in United States history. About 620,000 people died in the Union and the Confederacy combined; about 500,000 more people were wounded. Wounds to extremities, like arms or legs, were the most common injury among soldiers in the Civil War. Shattered bones, lodged bullets, and infection from rifle shots were also common wounds. Civil War surgeons were under-trained and underprepared for the fast-paced environment of a wartime hospital. Germ theory was not yet established, and surgeons often operated for days with no sleep. There were also many soldiers in the hospitals who were injured and needed help. The surgeons often amputated and dressed the damaged limbs to treat injuries and prevent death by infection. 75% of all operations performed during the Civil War were amputations. The survival rate for amputation was actually high (75%) despite unsanitary conditions and rampant infection, though many soldiers who survived amputation became disabled as a result. Acquiring a disability changed veterans of the Civil War. Many soldiers were civilian volunteers and before the war were farmers and other types of manual laborers that supported families. They depended on the ability of their body to complete their work and having a disability made that very difficult. Mental disabilities from the war, like post-traumatic stress disorder, affected soldiers in the same way. The lives, relationships, and opportunities of disabled veterans were very different after the war. The Civil War became an important marker for the history of people with disabilities in the United States.

Types of Acquired Disabilities

Limb amputation and other damages inflicted from battle were documented frequently during the Civil War. Veterans who became disabled as a result were likewise documented. All types of soldiers in both the Confederacy and the Union acquired disabilities of this type. Amputation of one or more arms or legs, or removal of the eye(s) were not uncommon. Veterans with damaged eyes became visually impaired, had low vision, or experienced blindness. Veterans with arm and/or leg amputations experienced symptoms related to their surgery, like less function and mobility. Pain was also chronic in many cases. Resections (the surgical removal of bone, tissue, or muscle) in battlefield hospitals around amputation sites were completed quickly. The goal was to finish successfully and to save the patient’s life; the patient’s comfort was not a long-term goal of the procedure. Veterans who survived amputation often experienced pain around the site. This pain was made worse when artificial limbs like wooden legs and arms (known as prosthetics) became more widespread after the war. Resections led to prosthetics that hurt and were uncomfortable for veterans to use. Prosthetics were also big, heavy, oddly-shaped, and uncomfortable in most cases. They helped restore function, but they presented their own problems. Injuries combined with field surgery caused veterans to have other types of disabilities, too. Soldiers with injured bodies could also experience organ problems throughout their lives. Tiredness, sickness, loss of feeling, pain, and other lifelong problems were also documented among Civil War veterans.

Other types of non-visible disabilities harmed veterans after the Civil War. Mental disabilities were another “damage” that could affect a former soldier. Veterans of the Civil War were often diagnosed with different illnesses that are known as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, or PTSD, today. According to the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, “PTSD is a mental health problem that some people develop after experiencing or witnessing a life-threatening or traumatic event.” Harmful and stressful events could impair a soldier’s mind. PTSD symptoms in Civil War veterans were identified as “irritable heart,” or “nostalgia.” “Delusion” was also a common psychological disability that resulted from the high-stress of war and fighting. It caused those with it to experience a different sense of reality from most people. “Melancholy” was another mental disability. Soldiers with melancholy had little energy and were often sad or angry. They might not have eaten or they may have tried to hurt themselves. Melancholy is like depression by today’s standards.

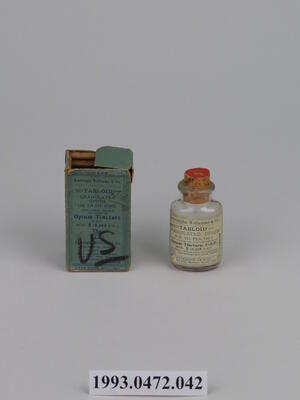

Psychological disabilities related to physical ones also affected soldiers and veterans. Phantom pain is one such disability. Phantom pain is the sensation of pain in an amputated arm or leg. The pain comes from a part of the body that is no longer there. It is common among amputees. Phantom pains often caused veterans to use alcohol or drugs (like opium) to help ease their constant pain during and after the Civil War.

Addiction also served as a combination of physical and psychological disability. Surgeons will give a patient something to make the surgery less painful or make them sleep in surgery. This is known as anesthesia. Surgeons who performed amputation surgery during the Civil War gave patients anesthesia known as opium. Opium is highly-addictive to those who use it. It is a plant-based drug known as an opiate that relieves pain when administered. About 10 million opium pills were used by the Union Army alone during the Civil War. Many veterans of the war developed a physical dependence on opium. They became addicted to it as a result of its use in Civil War medicine. Doctors overused opium to treat sore joints, amputation sites, or other war-related injuries. Inability to use opium when desired led to withdrawals. A withdrawal is when one’s body is missing something that it thinks it needs. Withdrawals can make people sick, upset, and experience pain. Soldiers remained addicted to opium after their treatment had ended. They did not want to experience pain or suffer withdrawals. Kate Cumming was a famous Confederate nurse who treated injured soldiers. She talked about the overuse of opium in treatment of Confederate soldiers. “Much of that [opium] is administered; more than for their good, and must injure them.” Overuse of opium among doctors and patients continued for many years. It was not reduced and reversed until the 1890s. Alcohols such as whisky were also used in Civil War medicine. They were used on the battlefield to numb wounds and treat pain. Their use in pain treatment created a substance dependence similar to opium among veterans during and after the war as well.

Guided Reading Questions:

- What was the percentage of veterans who survived amputation surgery?

- What was "melancholy?" Does it have a modern equivalent?

- What was one addictive substance used in Civil War medicine?

References:

Bonnan-White, Jess, Jewelry Yep, & Melanie D. Hetzel-Riggin. “Voices from the past: Mental and physical outcomes described by American Civil War amputees.” Journal of Trauma & Dissociation: the Official Journal of the International Society for the Study of Dissociation (ISSD), 17(1), 13–34. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2015.1041070

Edwards Laura C. Dead or Disabled: The North Carolina Confederate Pensions 1885 Series. Wake Forest N.C: Scuppernong Press. 2010.

Gettysburg National Military Park. “National Disability Employment Awareness Month: A Civil War Connection.” The Blog of Gettysburg National Military Park. October 31, 2014. https://npsgnmp.wordpress.com/2014/10/31/national-disability-employment-...

Gillam, F. Victor, 1858?-1920, Artist. Throwing light on the subject Uncle Sam to old soldier -- "I'm not after you; I'm after the rascals behind you" / / Victor Gillam. 1898. New York: Sacket & Willems Litho. & Pt'g. Co. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2015645585/.

Gorman, Kathleen L. “Civil War Pensions: History of the Union federal and Confederate state pensions systems.” Essential Civil War Curriculum. Blacksburg, VA: Virginia Center for Civil War Studies.

Grant, Susan-Mary. “The Lost Boys: Citizen-Soldiers, Disabled Veterans, and Confederate Nationalism in the Age of People’s War.” Journal of the Civil War Era 2, no. 2 (2012): 233–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26070224.

“Legs for Soldiers.” The Tri-Weekly Standard (Raleigh, N.C.), Jan. 19, 1866. Edition 1. Page 2. https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn85042143/1866-01-19/ed-1/seq-2/

“Lenoir Family Papers, 1763-1940, 1969-1975.” Southern Historical Collection. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/00426/

Logue, Larry M and Peter David Blanck. Race Ethnicity and Disability : Veterans and Benefits in Post-Civil War America. 2010. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Marten, James Alan. Sing Not War : The Lives of Union & Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America. 2011. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. https://library.biblioboard.com/content/55a04edd-0a99-48ef-94e8-b1e89166....

Newman, William. “Result of Appointing a Veteran as Postmaster.” Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. February 11, 1865. Still image, text. Gettysburg, PA: Special Collections and College Archives, Musselman Library, Gettysburg College. https://library.artstor.org/asset/SS7731291_7731291_10903867.

Nielsen, Kim E. A Disability History of the United States. 2012. Boston: Beacon Press.

“Peculiar Accidents.” The Farmer and the Mechanic, part of The State Chronicle (Raleigh, N.C.), June 16, 1881. https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn85042098/1881-06-16/ed-1/seq-3/

“Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and the American Civil War.” National Museum of Civil War Medicine. May 2, 2019. https://www.civilwarmed.org/ptsd/

Reilly, Robert F. “Medical and surgical care during the American Civil War, 1861-1865.” Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). Vol. 29 (2). 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4790547/

Sauers, Cameron. “To Remake a Man: Disability and the Civil War.” The Gettysburg Compiler. April 9, 2019. https://gettysburgcompiler.org/2019/04/09/to-remake-a-man-disability-and...

Somerville, Diane Miller. Aberration of Mind: Suicide and Suffering in the Civil War–Era South. University of North Carolina Press, 2018. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469643588_sommerville.

Wegner, Ansley Herring. Phantom Pain : North Carolina's Artificial-Limbs Program for Confederate Veterans : Including an Index to Records in the North Carolina State Archives Related to Artificial Limbs for Confederate Veterans. 2004. Raleigh N.C: Office of Archives and History, N.C. Dept. of Cultural Resources.

“Who Fought?” American Battlefield Trust. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/who-fought